Recently, I came across a disturbing article on Tibet – an interview with Dr.Gyal Lo – a renowned Tibetan educator and activist. In his interview with Marco Respinti, Dr. Lo highlighted how education policies in Tibet under Chinese rule are destroying this ancient culture.

At one level what Dr. Lo pointed out was not a total surprise. We know the Chinese authorities did not encourage teaching the children the Tibetan language and culture. Still the stark dangers of losing a five thousand year old precious culture was sad and shocking.

All Starts at School: Dr.Gyal Lo Denounces the CCP’s Genocidal Policy in School

This interview galvanized me to complete an essay I had started several months back – a look at the challenges of Tibetan cultural preservation and the efforts to overcome them. Even though the dangers Dr. Lo highlight are real, somehow, I will cling to hope. I will draw inspiration from our resilience and determination over the past sixty years. I’m going to hope that we still find a way to keep our culture.

In 1959, the People’s Liberation Army of China completed the final occupation of Tibet and forced its leader, HH The Dalai Lama, to flee into exile. An estimated 80,000 Tibetans followed him to lead new lives as refugees in a foreign country. Sixty years later, while the Tibetan culture in Tibet is endangered in the face of sustained cultural genocide, it is being preserved and even rejuvenated in exile! This article is a celebration of this fantastic achievement.

The miracle is that we brought about this transformation even as we went through one of the darkest periods in our history. For two generations, we have been hounded from our homeland, driven into exile, and stripped of our monasteries and even our dignity. We have no idea when even a beginning to resolving the Tibetan issue might occur. Therefore, we have no real hope that it will happen in our lifetime.

In exile, it is impossible to overestimate the struggles and challenges of the first-generation refugees. They were catapulted by the Chinese aggression into a foreign country with no language or work skills to succeed in the new country. Most started their new lives as road construction laborers working at minimum wage. It was a massive change in their lives – from the cool pastures in Tibet to the heat and humidity in India. Many did not survive – victims of their newfound poverty and tuberculosis. Yet, the majority found a way to survive, rebuild their lives, and cling to their identity and culture.

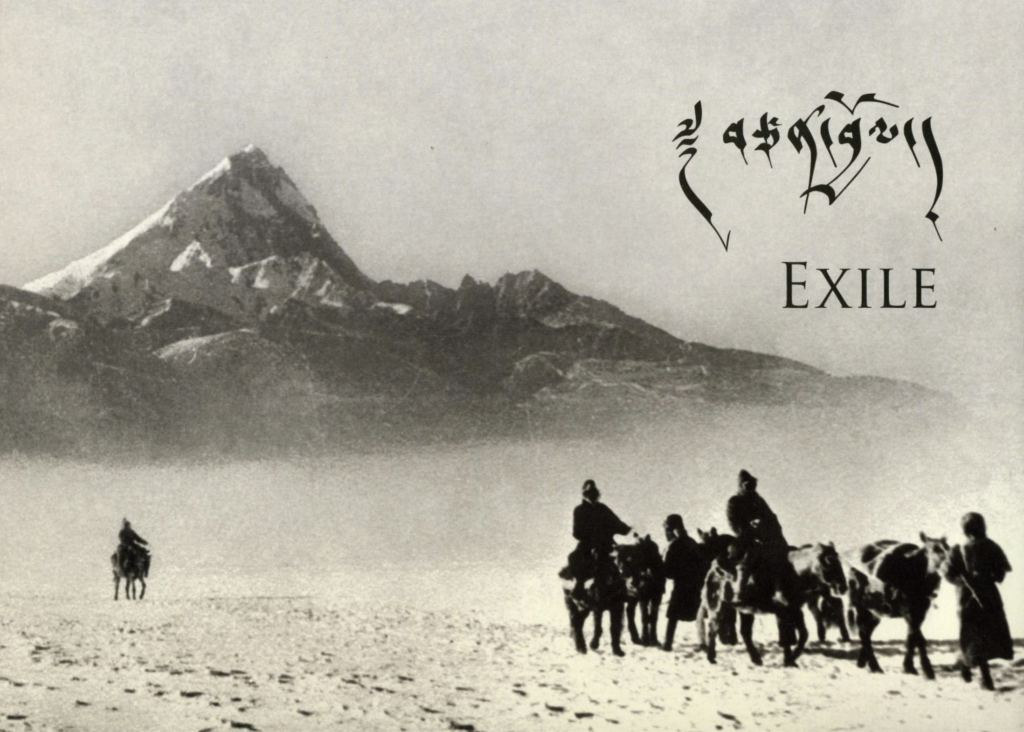

Last summer, a longtime friend, VJ Supera, gifted me a magnificent book titled Exile by Lobsang Gyatso Sither on her return from her travels. It is a beautiful photo journal that traces our exodus into exile in 1959, right through our early rehabilitation in India up to 1989. As a photo journal, it is disconnected from the individual emotions of the struggles and challenges of families. Still, it has an amazing collection of historical photos beautifully framed with well-researched texts – and it took me to those days of extreme struggle. Viewed in the background of those challenges, the story of Tibetan cultural preservation in exile is all the more remarkable.

One of the key reasons behind the success of Tibetan cultural preservation in exile was the vision and wisdom of HH, The Dalai Lama, and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India. In their early meetings, two vital decisions helped shape the landscape of cultural preservation – to set up exclusive Tibetan refugee settlements and to have separate schools for Tibetan children.

India has vast powers of assimilation. Throughout history, kings and emperors who came to conquer and defeat India have assimilated into this land’s mosaic. A hundred thousand Tibetans could have so easily been swallowed up. Instead, every Tibetan refugee settlement in India is a little haven of Tibetan culture. In them, Tibetans can be comfortable in their skin, comfortable being Tibetans. It gives them the liberty to string hundreds of prayer flags over every rooftop, build stupas, temples, and monasteries, and even have a community calendar built around the Tibetan way and what is important to them.

In the same way, having separate Tibetan schools was a game-changer for the children. The seeds of Tibetan cultural transmission in exile were decisively sown in that crucial decision. I want to underline the depth of wisdom and highlight the impact of this decision because I don’t think it has gotten the attention and acclaim it so thoroughly deserves. Imagine if a different decision was taken to accommodate small groups of Tibetan children in Indian schools run by the government. With either English or Hindi as the medium of instruction, and with either of those languages being the language of use in all interactions, Tibetan students would quickly learn these but perhaps lose their mother tongue in the bargain. Social scientists will tell us that the loss of language is the precursor to the loss of culture.

Instead, over the past fifty-odd years, the Tibetan community in exile built close to a hundred schools. It is no small achievement. It took HH The Dalai Lama’s leadership and tremendous goodwill and support from India and international aid organizations. I believe that adversity brings some coping mechanisms; it gives strength and resolve to the strong ones. We Tibetans were somehow so blessed during those early years in exile to have people like Amala Tsering Dolma, the elder sister of HH The Dalai Lama, Pala, and Amala Taring, among others. These people met the challenges of providing for and educating the early wave of Tibetan refugees in India. They did it with quiet dignity and determination, making a massive difference for all of us. I know this because I was a frightened and confused six-year-old in one of the shelter schools at Dharamsala way back in 1963.

In remembering and celebrating our achievements, I feel it is vital that we do not forget our foundations or the people who laid them. Whatever the celebrations – the development of our schools, monasteries, the building of settlements, or even building and improving infrastructure for the Government in Exile at Dharamsala, I believe every successive administration builds on top of the hard work and achievement of the previous one. From that perspective, I always feel massive gratitude to HH, The Dalai Lama, and those around him during our earliest days in exile. Going back to Tibetan schools, I would be remiss if I did not mention the exceptional contribution of Amala Jetsun Pema. She has been a towering pillar of strength for us over all these years.

Together with the monasteries, our schools became the sanctuaries of our culture. In 1991, Tibetan educators took the momentous decision to switch the medium of instruction at the primary level from English to Tibetan. This Tibetanization of education was a direct attempt to use our schools to help transmit our culture. So textbooks were printed in Tibetan, images were Tibetanized, and teachers were specially trained to teach in the Tibetan medium. Almost all schools had one or more Tibetan religious teachers, and Tibetan dance, drama, and music were part of the core curriculum in our schools.

Many of our schools, especially boarding schools like the TCV group, became vibrant and thriving Tibetan communities and centers for nurturing our culture. The students were taught by Tibetan teachers and nurtured by loving Tibetan foster parents. Together, we were a community; it was exceptional, and I know this because I was part of one. The teachers and students felt a special kinship and connection because of our shared destiny as Tibetans in exile. It is no wonder that Tibetan parents in Tibet themselves wanted their children to grow up in these schools and be grounded with love in their own culture. For many years, thousands of children risked everything and secretly crossed the Himalayan passes for a shot at education in one of the Tibetan schools in exile!

While the story of our schools is inspirational, in some ways, it pales in comparison to the growth of monasteries. In exile, we’ve built over three hundred monasteries. For every school we built in exile, we created three monasteries! I remember this story of an early European volunteer in one of our primary schools in exile. He spent a couple of years in that school and then returned home. Several years later, he returned to find that the small primary school had grown into a middle school. He was happy at this moderate growth until he visited the community to see three beautiful monasteries. Then the progress of the school’s development did not look quite so impressive!

But as Tibetans, of course, we understand. Religion is our very breath – it is what we hold the dearest. So, from our perspective, the number of monasteries built in exile is a testament to our devotion and the great blessings, charisma, and resourcefulness of our spiritual masters. Starting from HH, The Dalai Lama, we are fortunate to have many great spiritual masters and leaders.

While the Western world focused on Science and Math and built great learning centers like Harvard or Eaton, we focused on spiritual learning in Tibet. In place of universities, we created lovely monastic centers like Sera, Gaden, Drepung, and Tashi Lhunpo. Tens and thousands of monks studied in them, all pursuing spirituality and human consciousness. The Communist occupation of China destroyed our centers of learning, and today, there are only a few monks in those iconic places. The miracle is that the Tibetans in exile have built all these beautiful monasteries again! We’ve rebuilt them, and today, there is a Sera, a Drepung, a Gaden, and a Tashi Lhunpo right here in India. These are, again, vibrant learning centers with thousands of monks in them. If we stop to pause, we have many reasons to celebrate.

The rebuilding of institutions in exile reflects and manifests the love and reverence we had for them in the first place. In so far as I know, there was no grand central plan. Our Rinpoches – our spiritual masters and communities built them when they could. Many were spontaneous and organic, coming together when desire and resources came together.

In the Tibetan settlement at Clement Town, the first monastery that came up was the Tashi Kyil Monastery. Many of the earliest settlers were from Amdo. So, this monastery was inspired by the original Tashi Kyil Monastery back in Labrang, Amdo. Several years later, we had the immense good fortune to have HH Trichhen Rinpoche of the Mindroling lineage settle here. Now, we have the fabulous Mindroling Monastery here. This monastery, together with the Great Stupa and the adjoining complex, is now a tourist destination for Uttrakhand.

These two institutions are just a tiny example of a fabulous trend. In India and Nepal, Tibetans are rebuilding many of the institutions they left behind in Tibet. Dharamsala, the Government in Exile seat, has taken the lead and rebuilt several of them. The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) trains young Tibetans and showcases Tibetan performing arts. TIPA is also the best source of qualified teachers for our schools’ Tibetan Dance, Drama, and Music programs. The Norbu Linka Institute of Tibetan Culture teaches several traditional Tibetan art forms like woodcarving and thangka painting. Mentse-Khang, the Tibetan Medical and Astro Institution, trains aspiring Tibetan doctors in Sorig – or the conventional Tibetan Art of Healing. Today, there are Tibetan herbal clinics in hundreds of locations in the subcontinent, treating and healing not only Tibetans but tens and thousands of Indians.

These temples, monasteries, institutions, and schools that we have created in exile are at the heart of our culture. The sight of prayer flags flying from every rooftop, the tapestry, and icons in the monasteries, along with giant prayer wheels and colorful stupas, all convey the subliminal message of Tibetan culture to our children and everyone who comes in contact with it.

Over the last twenty years, another wind of change has swept the Tibetan exiled communities in India and Nepal – a trend to immigrate to the West. It started in earnest when the US government decided to give one thousand immigration visas to Tibetans in the early nineties. Since then, there has been a steady but persistent push, and every year, the population of Tibetans in the Diaspora in the West continues to grow. This presents a new and fascinating challenge to Tibetan cultural preservation. Here in the West, we no longer have the luxury and comfort of exclusive Tibetan settlements. As immigrants, we blend and fit in wherever we can – isolated Tibetan individuals or families in various neighborhoods in America and Europe.

The challenges of cultural preservation are different, yet if the early indicators are anything to go by, we are giving ourselves a fighting chance. Even in the face of all the challenges that immigrants routinely face – documentation, employment, and housing, among others, Tibetans are finding ways to build communities for themselves. Whether in big immigrant cities like New York or Toronto or more rural states like Montana or Idaho, Tibetans are forming associations, building Tibetan language schools, coming together to celebrate festivals, and exploring ways to teach the culture to the children. It is fascinating and encouraging to see the trends, and worth a full exploration later on. I can write today that if the Tibetan resolve and resilience in the subcontinent is any indicator, then there is hope and optimism that we will find a way to keep our culture in the Diaspora in the West. Hope is a beautiful commodity for us right now!

His Holiness The Dalai Lama once described the various races and cultures of the world as the garden of humanity. I love that imagery – and think that the Tibetan culture would be a small but beautiful flower in that garden. I believe that all cultures are beautiful and that every one of them contribute wisdom and beauty to the collective fabric that is our earth.

Sharing Tibetan Culture – by Karma Tensum